Art is something that is subjective in so many ways and almost impossible to define. The formaldehyde preserved animals of Damien Hirst and the unmade bed of Tracy Emin are in some ways less complicated than a Caravaggio or Michelangelos David, but in others infinitely more so. Some pieces scream out their creators inner torment, others the creators peace with the world and appreciation of nature and beauty. The Usher gallery houses art of many schools, but the question I find myself asking is this. Can our performance be considered a piece of art in itself. On the level of personal reflections it may perhaps fail, certainly it is not an expose of the groups minds, no insight into tortured souls or placid contentness, yet on another level it was never intended to be. As an insight to the condition of humanity, the time driven, regulated nature of modern working life being the focus of the piece, it spoke not a truth about the individual creators but rather one about western society as a whole. It shows how as a society founded on the principles of freedom and democracy we are still slaves to one thing: ourselves.

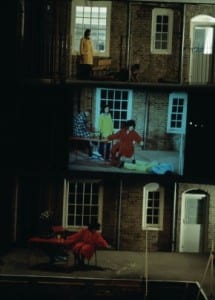

Another objection that may be given about our piece is that its legacy could be considered to be short lived. Unlike the Greco-Roman sculptures situated on the floor above us after we performed, our piece will not be there generations after our deaths, it was not even there after the gallery closed that night. Yet I do believe that it would be unfair to argue the piece had no legacy. If one person who viewed it walked away with a changed thought process then the legacy of the piece is undoubted. In the words of Henry David Thoreau “It’s not what you look at, it’s what you see.” As a physical piece, what you see (or saw) will have changed depending on the timing of your visit to the gallery. Yet as a multi-faceted exhibit, I would be forced to argue with Thoreau partially and say that what you looked at will have been key to what you saw. To look at the decaying pineapple may have inspired feelings of the awareness of ones own mortality, to stare at the ravishing effects time has upon organic matter. The human clock on the other hand shows how time can preserve someone, how through the create of something simple, you can become more than just yourself, something that is separate from you, a legacy that time can’t take from you, something that is yours after you are gone. To observe us, the performers could envoke feelings of ennui, even despair as the pointless, repetitive, circular nature of the day is played out, perhaps even striking a realisation that the lives being portrayed are likely similar to their own. Or you could see none of these things. But the possibility of there being these reactions and indeed that there was negative and positive responses heard throughout the day shows that thoughts could undoubtedly be provoked.

Of course, following these arguments, you could say that any public displays are a form of art. A premiership football match can invoke strong feelings of passion, stirring people to emotional highs and lows that are disproportionate to an event they played no part in. Similarly, the novels of a great writer or the food of a great chef or the buildings of great architect can all stir emotion. Yet I believe that they cannot be considered art, whilst the collection of possessed time can be. The aforementioned events do not aim to provoke the thoughts of their observers and participants, whereas that was our aim from the start. Had we failed to excite the thoughts of our audience then our purpose would have failed, whereas all of the above could still consider themselves a success.

Another somewhat crude argument is that we were displayed in an art gallery, that alone making us considerable as a piece of art. Then again, it could be counter argued that the Vatican is almost as far removed from an art gallery as it is possible to be and yet the Cistine Chapel most be considered amongst the finest art work in the world. Many pieces of modern art are utilitarian items simply displayed in an unusual or unconventional context. By this measure, anything can be considered art so long as it is presented as such. The role of the public is also an important one, for should a thing widely be considered to be something, then generally it will be held up as such, regardless of it’s original context. Here, one is reminded of reader theory in literature which argues that a piece of writing is no longer the intellectual property of the author as soon as he or she has written and published it. Hopefully a fate that will escape this blog as one only wonders at the sort of individual who consider this trite exploration of artistic preferences suitable to intellectually commandeer!

Ultimately, as I said at the beginning, to define whether a thing is art in itself or not is a nigh on impossible task, ultimately it comes down to two people. The viewer and the attempted artist. I am personally unsure as to the exact nature of what we created, but I do think it had a beauty, a relevance and a grace that some art pieces I have seen lack. So perhaps I am an artist, or perhaps I am a pretentious fool with delusions of grandeur and a blog to write. Ultimately, the decision is out of my hands.