During most museum visits you meander through the exhibits occasionally reading a thing or two and possibly even have a chat about what you have seen however this is changing. Catherine Hughes believes that ‘museums are theatres, rich with stories of human spirit and activity and the natural forces of life… both museums and theatre present us with ourselves in different contexts, holding the mirror up and showing us what we have done and what we might do (Hughes 1998, P. 10).

Performances in museums by actors are becoming increasingly popular, with our piece Possessed Time being an example of this. The parallels have always existed between museums and theatre, the whole idea that an audience goes to see something that they will hopefully find engaging, but now the two have become to merge and the distinctions between the two may be obvious although at a small number.

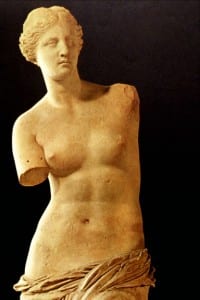

Susan Bennett observes, ‘… theatres and museums have increasingly become symbolic and actual neighbours, sharing the task of providing entertaining and educational experiences that draw people to a district, a city, a region, and even a nation’(2013 p. 3). They both serve a similar purpose and both work together to create a culture that is symbolic of the area in which they are situated. Moreover, ‘exhibitions are fundamentally theatrical, for they are how museums perform the knowledge they create’ (Kirshenblatt-Gimblett 1998, p. 3). The parallels are clear, they both serve the same purpose they just have always done it in different ways, and now that live action is happening in museums theatre has bled a new dynamic into them. When performing Possessed Time people stared and looked at us and try to understand what we were saying and what our purpose was as if we were a painting or a sculpture.

As well as differences between the two buildings, such as the audience in a theatre being on one side as they sit and watch the actors on the other, there are also differences between theatre on the stage and a performance in a museum. In a theatre ‘the subject matter of the play bears no relationship to the premises in which the play is performed’, whereas in a museum, ‘the subject matter is related to the museum as a whole or the exhibit’ (Bridal 2004, p. 9). If we performed our piece in a theatre, it would have had half the impact compared to Gallery 3 because all our influences and process were based on the things we discovered in that space. Furthermore, ‘museums traffic mostly in material designated as representing the past, while theatrical performance takes place resolutely in the present, ephemeral, resistant to collection’ (Bennett 2013, p. 5).

I believe that although they will forever be separate entities now that theatre has started to become part of the museum experience, the two will become ever more indistinguishable.

Written by Shane Humberstone.

Works Cited

Bennett, Susan (2013) Theatre and Museums, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bridal, Tessa (2004) Exploring Museum Theatre Oxford: AltaMira.

Hughes, Catherine (1998) Museum Theatre: Communicating with Visitors Through Drama, Portsmouth: Heinemann.

Kirschenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara (1998) Destination Culture, London and Los Angeles: University of California Press.