After our performance we received feedback and it was interesting that our performance was interpreted from a feminist view and this brought a cause for thought. It seemed that we channelled a similar message to that of the Guerrilla Girls through our costume and powerful impact of our performance. The femininity of our 1920’s costume, through the use of stockings, elegant dresses, pearls and the red lipstick made it clear to our audience that we were women while the balaclavas hid our true identity. In a sense we were women disrupting a mans territory as The Usher Gallery was named and built for James Usher who was a man and a vast amount of the art displayed have been created by men, it could be said we were making a feminist statement against the over whelming amount of men who control , create and are praised for art. The Guerrilla Girls are similar in the fact that they hide their identity through the use of gorilla masks and disrupt galleries just the way we did in our performance.

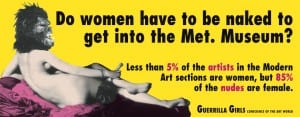

As Kathe Kollwitz explains how the Guerrilla Girls began: ‘In 1985, The Museum of Modern Art in New York opened an exhibition titled An International Survey of Painting and Sculpture. It was supposed to be an up-to-the minute summary of the most significant contemporary art in the world. Out of 169 artists, only 13 were women. All the artists were white, either from Europe or the US. That was bad enough, but the curator, Kynaston McShine, said any artist who wasn’t in the show should rethink “his” career. And that really annoyed a lot of artists because obviously the guy was completely prejudiced. Women demonstrated in front of the museum with the usual placards and picket line.’ (Guerrilla Girls 1995) It is evident from the statement that the reasoning behind the Guerrilla Girls is to protest against the lack of praise for women and the sexism in art, politics and pop culture. In a way us disrupting the gallery in the way we did and creating such an impact to the point where passers by would stop to see our performance shows how we raised a similar message through our use of costume but aggressive stature, focus and movement.

What perhaps diminished the feminist message from our performance is the fact we smuggled in The Big Ben which could be seen as quite a phallic symbol due to it’s shape but also it’s association with Westminster which has a higher ratio of men to women. The reason behind smuggling The Big Ben into the gallery was not in relation to a feminist message but to smuggle a different cities culture into Lincoln and as The Big Ben is symbolic of London we thought it would befit the site.

If we were to do the performance again we would definitely look at it from more of a feminist point of view. The costume we had chosen and the use of sound scape were affective and had great impact on the gallery and our audience but we would have to re-think the object we would smuggle and if we’d smuggle anything in at all. I was thinking perhaps posters with a feminine message on them that could be stuck around a gallery, or perhaps a sculpture that was created by a woman of power, maybe one of Joan of Ark? It would be interesting to look into Guerrilla Girls as a source of inspiration Even so we feel that our performance was a success and had the impact that we intended to create from the moment we sped up to the gallery in our get away car to us leaving the gallery as elegant ladies of the 1920’s.

Works Cited:

Girls,Guerilla (2011) Guerilla Girls, Online:

http://www.guerrillagirls.com/interview/index.shtml (assessed 10 May 2013).